Who cares about Berkshire's emissions?

Form versus substance in climate reporting

One-Liner: A shareholder proposal headed to a vote at Saturday’s Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting calls for the company’s utility subsidiary, Berkshire Hathaway Energy (BHE) to disclose Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, and “steps to be taken” to reach net zero. That sounds compelling, but, digging in, it’s apparent that this ask is about form over substance - Berkshire already publishes the key data1, and, even if they didn’t, it can be reconstructed from US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data (which I walk through in the piece).

Thousands of investors will descend on Omaha over the next few days to attend the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting (AGM) on Saturday. It’ll be the first Berkshire AGM without the company’s late vice chair, Charlie Munger, sharing the stage with CEO and chair Warren Buffett. Understandably, the financial press is focused on succession issues - see, for example, this Financial Times piece comparing Todd Combs and Ted Weschler’s stock picking record to Buffett’s (“Can any stockpicker follow the Oracle?”).

(Financial Times)

Berkshire, like other mega-cap companies, has been a major target for activist shareholder proposals in recent years. Climate-related resolutions have gone to a vote at every AGM since 2021. That trend will continue this year, with two 14a-8 proposals on climate and environmental issues slated for a vote, plus two proposals focused on social issues (one on diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at Berkshire and another on labor relations at the company’s railroad subsidiary, BNSF), and two so-called “anti-ESG” proposals.

(SEC Filings)

Because Berkshire Hathaway’s activities are so wide-ranging, it offers a lot of surface area for activists concerned about the company’s approach to sustainability.

Climate change-induced natural hazards could impact the risks underwritten by the company’s insurance businesses (GEICO, Berkshire Hathaway Primary, and Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance).

Berkshire has a wide range of equity investments, including in emissions-intensive companies and industries (for example, Occidental Petroleum). So, arguably, there are “financed emissions” lurking in Buffett’s portfolio.

BNSF, though inherently lower-emission than competing modes of transportation, consumed ~1.1 billion gallons of diesel fuel last year, implying ~11 MT of CO2 emissions, about a third of US railroad emissions.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy (BHE) is a holding company within a holding company that owns a mix of (i) bundled utilities, (ii) competitive generation assets, and (iii) pipeline and transmission assets. Its US electric utility and natural gas businesses emitted ~53 MT CO2 in Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions in 2023, plus an additional ~9 MT in CO2-equivalent CH4 and NOx emissions.

Grossing up total emissions for Berkshire’s industrials business (Precision Castparts, Lubrizol, etc.), based on the 10-K’s assertion that BNSF and BHE represent “more than 90%” of the company’s overall emissions, implies at least ~75-80 MT of direct and purchased-energy emissions across the company.

(Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report)

This year, I’ve been thinking a lot about the value of emissions reporting. On the one hand, standardized metrics are really useful; it would be hard to analyze public-company emissions at all without guidance on Scope 2 and Scope 3 reporting via the World Resources Institute’s Greenhouse Gas Protocol, or the standardized CDP questionnaire, which many companies post publicly (see, for example, CDP responses from Apple, Alphabet, and Meta).

But on the other hand, emissions are an output, not an input. They can sometimes be a useful scorecard, but on their own, they don’t reveal much about why emissions are going up or down, or how they could be reduced in the future. The key driver of the energy transition will be companies making long-term investments that unlock (i) electrification and (ii) clean electric generation. This doesn’t always align with the ups and downs of annual emissions reporting. Some investments have a short-term emissions payoff, but lock in fossil infrastructure (e.g. making incremental efficiency improvements to a blast-furnace steel mill), while other investments enable long-term emissions reduction without making a short-term impact (e.g. electrifying your company’s operations in a geography with a coal-heavy grid).

Beyond a certain minimum threshold of completeness, climate and environmental disclosures should be aligned with how climate and environmental drivers intersect with financial value drivers. For example, procuring clean, firm power is strategic for the leading cloud service providers (AMZN’s AWS, MSFT’s Azure, and GOOG’s GCP) as they continue to invest in energy-hungry data centers.

This is why I’m a bit puzzled by the climate proposal filed by the Illinois State Treasurer, which is headed to a vote on Saturday. The proposal targets Berkshire’s reporting on BHE:

Resolved: Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (the “Company”) request that its Board of Directors (the “Board”) disclose, in a consolidated annual report (at reasonable expense and omitting proprietary information) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions data by scope, as well as progress towards its net-zero decarbonization goal, for Berkshire Hathaway Energy (“BHE”).

(Berkshire Hathaway Proxy Filing)

The Treasurer’s argument for the proposal draws a distinction between BHE’s existing disclosures, which follow a template disseminated by the Edison Electric Institute (an electric utility trade organization), and the familiar “Scope” reporting endorsed by the GHG Protocol (emphasis added):

Given the widespread adoption of the GHG Protocol methodology by standard-setters and regulatory bodies, it is no surprise that other U.S. energy companies and comparable peers disclose emissions per the methodology, including Xcel Energy, The Southern Company, Duke Energy Corporation, and Sempra Energy.

BHE is a notable outlier, choosing to present emissions data by operating segments (i.e. owned generation and purchased power). This leaves the Company and shareholders at a disadvantage, as both are unable to accurately benchmark against peers, industry metrics, or market trends. Under the current disclosure method, such analysis and benchmarking necessitate the use of assumptions or imprecise estimations.

The Company also argues in its opposition statement that it believes that disclosure by scope is not necessary at this time. However, with the enactment of enhanced disclosure requirements—particularly from the State of California and the SEC—the Company will be required to do just that. It behooves the Company and BHE to revisit their disclosure methodology to ensure alignment with these disclosure requirements.

(SEC Filings)

For context, this is what BHE’s disclosures for the most recent year look like:

(Berkshire Hathaway Energy)

“Owned generation” plus “non-generation CO2 emissions” is substantively equivalent to “Scope 1,” while “purchased power” is substantively equivalent to “Scope 2.” I really struggle to see how reformatting this table radically enhances an analyst’s understanding of BHE’s emissions.

BHE’s emissions disclosures already include:

A breakout of CO2 emissions from owned generation and purchased power by electric utility subsidiary (PacifiCorp, MidAmerican, and NV Energy, plus BHE Renewables).

Methane emissions for the company’s natural gas assets, also broken out by subsidiary (BHE GT&S, Northern, Kern River, MidAmerican, and Sierra Pacific).

A consolidated version of each report with total emissions across each operating business.

The proposal also calls for Berkshire to disclose “steps to be taken in [BHE’s] decarbonization strategy to reach intermediate and long-term goals,” but, again, I am not sure what is missing after you take into account the long-term guidance the company shared as recently as last November, at the EEI’s annual conference (not to mention PacifiCorp and NV Energy’s integrated resource plans). It’s totally fair to object to the (i) level of ambition of BHE’s energy transition plans or (ii) Berkshire’s execution relative to that ambition. But to suggest there is a huge gap in the quality of reporting versus peers is misleading at best.

The deeper question all this raises is who are these disclosures for, and how will they be used? What I’m getting at here is that even if you completely sidestep the company’s sustainability reporting, the businesses that generate nearly all of Berkshire’s emissions - BNSF and BHE - are already covered by existing, publicly available energy and emissions reporting systems. In fact, these can be more timely and useful to an analyst than a typical large-cap public company’s ESG report.

BNSF, as a Class I railway, publishes an annual report on Form R-1 with the Surface Transportation Board (STB), which includes the company’s diesel fuel consumption down to the gallon. For Union Pacific (another Western rail network), locomotive emissions total ~96.5 percent of total Scope 1 emissions, and Scope 1 emissions total ~97.7 percent of combined Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Grossing up BNSF’s diesel emissions by a couple percentage points to solve for total emissions is not going to confound any kind of comparative analysis with other railways. It’s possible to use data from the STB and company filings to benchmark railway fuel use in an extremely granular way (and, incidentally to compare it to other modes of transportation), and to compare the results to key operating metrics like average train speed and yard dwell.

The data on BHE is even better. Analysts can estimate emissions intensities for all US emissions using EIA data on generation, and their own assumptions for the residual GHG intensity of purchased power. As a shortcut, I estimated emissions from purchased power by using the emissions intensity of IPP generation in each OpCo’s balancing authority. It’s possible to track utility emissions in the US on a monthly basis - a lot better than the typical 6-month lag companies publish their ESG reports on.

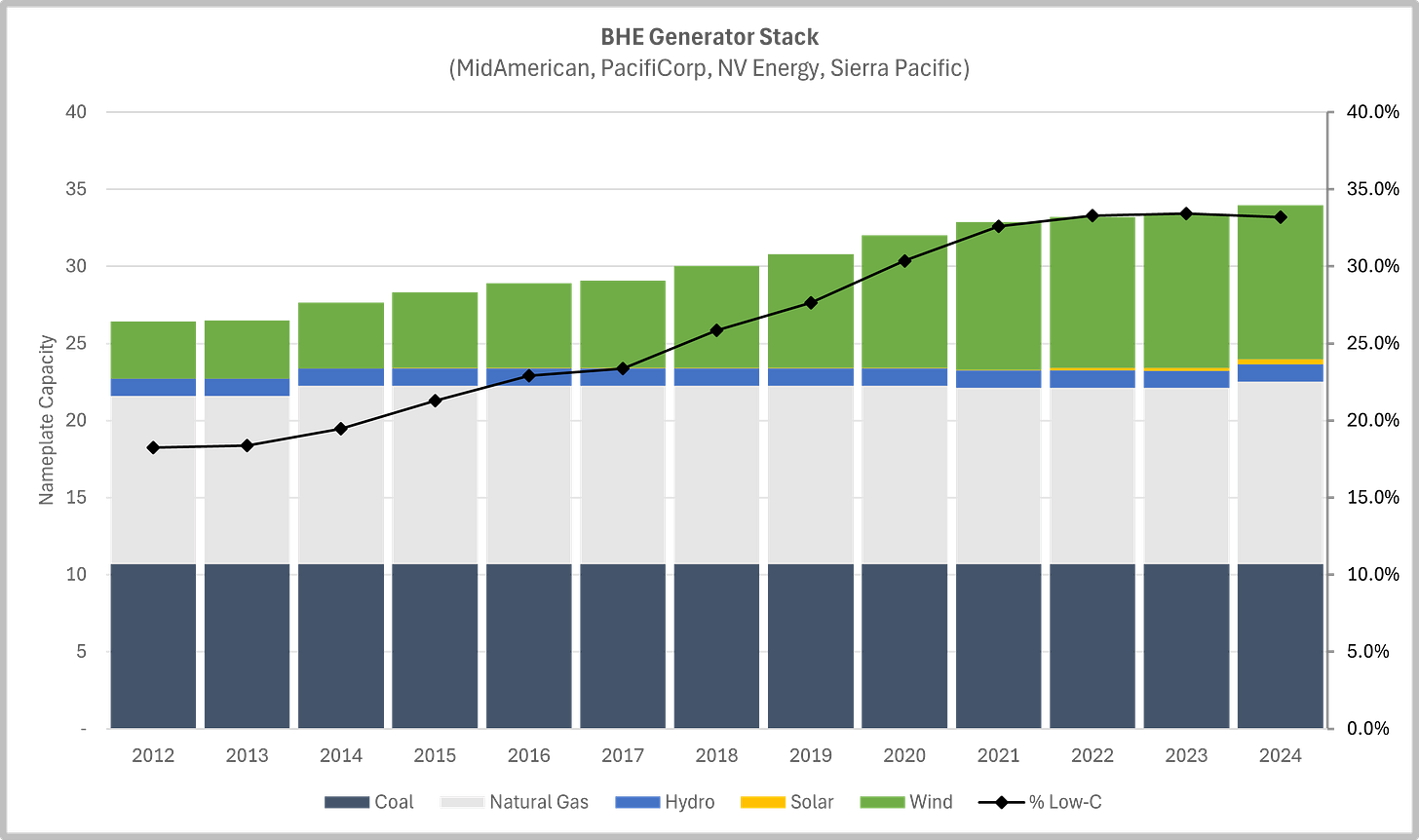

Comparing BHE’s bundled-utility subsidiaries to the broader universe of US investor-owned utilities (IOUs) what mainly stands out is (i) a slower pace of coal plant retirement, with less new gas capacity added as a result; and (ii) a higher uptake of wind power, which makes sense given MidAmerican’s footprint and history as an early adopter of wind. Looking at the current emissions intensity of BHE’s footprint, you see (i) two utilities in the middle of the third quartile of emissions intensity and (ii) one in the middle of the second quartile. None are standouts, in either a positive or a negative sense.

Finally, looking at trends over time, BHE has (i) reduced fossil generation, and, consequently (ii) absolute and intensity-based emissions faster than pure-play, publicly-traded peers.

Note: The data presented below only includes regulated utility subsidiaries of each company.

None of this is to say that Berkshire’s existing disclosures on ESG issues are perfect. This has been something of a point of pride for Buffett in recent years, who called activists’ suggestion to compile a consolidated climate change report for Berkshire “asinine.” The principle - that Berkshire is a holding company, and reporting on energy and environmental issues by its key subsidiaries that is in line with industry standards should be enough for institutional investors - is a fair one, but it begs the question of whether subsidiary level disclosures are any good (BNSF’s latest sustainability report is available here for those who would like to judge for themselves).

But again, this makes you wonder - what is this all about? What are greenhouse gas disclosures good for, anyway? All of the key sustainability issues at BNSF and BHE have a clear (digital) paper trail, out there on the EIA and STB websites, waiting for analysts to dig in. The Illinois Treasurer’s proposal calls for a modest repackaging of data that is already available to the public. No doubt this will make it a bit easier for data vendors and index providers to ingest Berkshire’s sustainability disclosures. But it feels a little small-bore when it comes to highlighting novel “climate-related risks and opportunities” for BHE - let alone Berkshire as a whole.

Disclaimer: This communication is for informational purposes only, and should not be construed as investment or proxy voting advice.

With the small exception of purchased-electricity emissions for Northern Powergrid, its UK-based transmission and distribution utility, which appear to be missing from BHE’s emissions reporting.