Shovels in the ground

The US government wants a new aluminum smelter

TLDR: Aluminum is one of the most energy- and emissions-intensive industries in the world. But thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act - the US’s flagship climate policy - the US could be close to adding its first new primary aluminum smelter in decades. Unpacking why this is happening helps illustrate how climate policy is merging with trade and industrial policy - and why analysts focused on “transition risk” may need to update their frameworks.

Last Monday’s Wall Street Journal featured an intriguing story about Century Aluminum (CENX), which is one of the last companies standing in the US primary aluminum industry. The US was the world’s largest primary aluminum producer as recently as 2000. But production has fallen by over 70% over the last 20 years, and some 2.8 MT of smelting capacity has been curtailed or permanently shut down.

Century – which was spun out of Glencore in the 1990s, and is still 43% owned by the commodity and mining giant – has not been immune from these industry trends, and in 2022 the company fully curtailed its Hawesville, Kentucky plant, which represents about a quarter of its production capacity.1 But now Century is talking about building a new smelter in the US, powered by renewable electricity, and with the aid of (1) a potential $500m grant from the Department of Energy (DOE) to offset construction costs, and (2) the 45X manufacturing tax credit for critical materials, part of the Inflation Reduction Act, which provides a tax credit for aluminum producers equal to 10% of eligible costs and, incredibly, does not expire.

Timna Tanners, the Wolfe Research analyst, asking the right question on Century’s Q1 2024 earnings call:

(Century Aluminum Investor Relations)

The cost of producing aluminum is closely linked with the price of electricity, which has made up 40-50% of Century’s cost of goods sold over the last few years.2 The challenge facing Century is how to make sure its new plant is low-carbon enough to make the DOE and other stakeholders happy, without making it uneconomic.

From the WSJ:

Though global demand for aluminum has grown by almost 5% per year, slightly faster than real GDP growth, the industry has struggled with rapid capacity expansion, especially in China, which has left US smelters operating at very low rates of capacity utilization – falling below 50% in 2009 and from 2016-2018.

(USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries)

Primary aluminum is made from virgin alumina rather than recycled scrap, the feedstock for the secondary aluminum industry. Aluminum smelting is one of the most energy- and emissions-intensive industries in the world, generating nearly 4 tonnes of direct CO2 emissions per tonne of output (compared to just 1.4 per tonne of steel).

On the other hand, aluminum is seen as a crucial input to the energy transition (this is why it’s eligible for 45X tax credits in the first place). Electric vehicles (EVs) are more aluminum-intensive than gasoline-powered cars. The industry’s own research suggests that in North America, the average pounds of aluminum per passenger vehicle will increase by a little over 10% from 2022 to 2030, which would be up over 20% from 2020. Transportation makes up a little over a third (35%) of aluminum demand as-is, so this translates to a ~3-4% tailwind to total aluminum consumption.

US trade and industrial policy around the aluminum industry has been focused on maintaining the country’s existing industrial base. The Trump administration imposed a 10% blanket tariff on aluminum imports in March 2018, with a goal of reaching > 80% domestic capacity utilization. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have imposed a wide range of anti-dumping and countervailing duty (“AD/CVD”) tariffs on various import categories. And now, with aluminum eligible for the 45X tax credit, and the DOE potentially offering to pay for 20-25% of the construction cost of Century’s proposed smelter, the US is pursuing a whole-of-government effort to make sure that new domestic capacity “pencils,” earning a healthy enough return to incentivize building it.

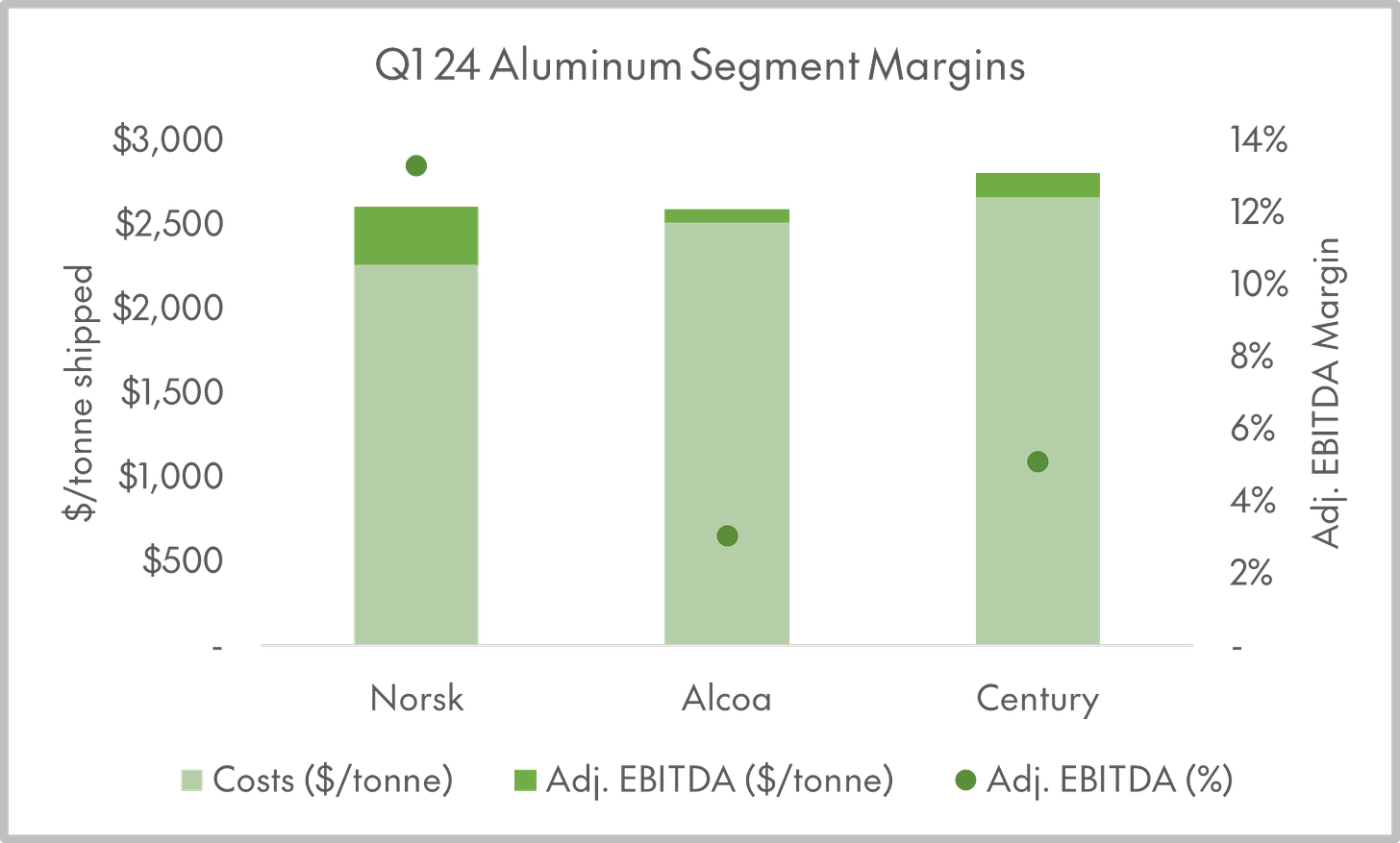

It should be pretty obvious at this point that aluminum smelting is not a very good business - at least not for the aluminum smelters. Norsk Hydro, which is the blue-chip Western producer, targets a modest 10% average return on capital employed through the economic cycle, despite sitting at the low end of the global cost curve for both alumina and aluminum metal.3 In Q1 2024, Norsk’s aluminum segment earned nearly 5x the margin (in EBITDA per tonne terms) of Alcoa’s comparable segment, and over 2x Century’s margins.4

Century, it should be noted, has higher costs per tonne than either Norsk or Alcoa, but this is partly mitigated by the fact that over half of the aluminum it ships comes from its US smelters, and therefore benefits from the Midwest Premium - which is basically the storage and delivery cost of selling into the US market. Shipments from its Grundartangi plant, in Iceland, fetched a price of $2,460 per tonne in Q1, versus $2,644 for output from its US smelters.

(Norsk Hydro Investor Relations; Company Reports)

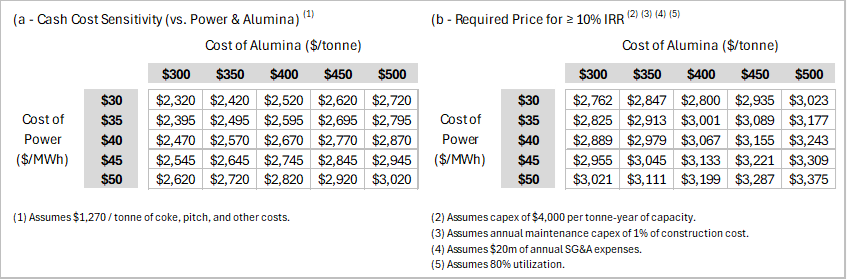

Back in 2018, Wood Mackenzie estimated that the cost to build new primary aluminum capacity in the West would be $3,000 - 4,000 per tonne-year. The US PPI is up 27% over 2018, so even after accounting for $500m in DOE grant funding, it is hard to see how the cost for Century could be much lower than $4,000 per tonne-year (in today’s dollars). The average price for aluminum delivered to the US is around ~$2,600-2,700 per tonne. So the math for a new Century smelter just barely pencils.

Ideally, Century will be able to secure long-term, low-carbon power for under $40 per MWh, and find customers who are willing to pay a modest “green premium” for their output. Even then, it seems like they would be able to just barely squeak out a 10% unlevered return on the project. And, to state the obvious, $40 per MWh would be an aspirational price. According to BNEF, offers for long-term solar power purchase agreements in MISO5 are currently in the $55-61 per MWh range - literally off the chart below.

(CAS Analysis)

What would the emissions impact of the new smelter be? In 2022, the most recent year with data, Century generated 2.53 tonnes of Scope 1 (direct) CO2e emissions per tonne of aluminum, and 3.71 tonnes of Scope 2 (purchased electricity) emissions per tonne. Even if Scope 2 emissions are de minimis, at 80% utilization, a new, 600,000 tonne-per-year plant would generate ~1.2 MT of additional emissions. Of course, if the plant’s output displaced imports produced with coal-fired electricity, building it would help reduce global emissions, even though it would increase total emissions (and, very marginally, emissions intensity) within the accounting boundary of the United States.

The main takeaway here is that a lot of legacy thinking on how to bridge “value” and “values” in investing assumes a somewhat idealized path to net zero, in which “transition risk” equals emissions. One of our core convictions at CAS is that this approach embeds a strong assumption about what climate policy will look like - one that aligns with a carbon-price (or -tax) driven approach. But as government spending on climate policy has grown around the world, it’s taken a different direction, one much more focused on trade and investment. The kind of climate strategies that are winning electoral (or at least legislative) mandates are also economic growth strategies. In the US, they are especially motivated by a desire to (1) create high-paying blue-collar jobs and (2) compete with China.

These dynamics can lead to the seeming paradox of using the IRA - a flagship piece of “climate policy” - to grow an industry that climate activists hate. This paradigm shift is full of opportunities for those who want the financial system to play a bigger role in combatting climate change. But they will need to be flexible about translating their arguments about climate impact into the language of climate risk, in a world where climate policy is also reindustrialize-the-US policy.

Hawesville was also the country’s only plant producing of 99.9% purity aluminum, the level used in “military aircraft, as well as in the lightweight armor plating found in many defense ground and weapon systems.” This is relevant because maintaining domestic supplies for aerospace and defense is ostensibly one of the main reasons for protecting the aluminum industry with tariffs and tax credits.

This is based on Indiana Hub and Nord Pool pricing for 2021-23, as reported in Century’s investor materials, and their disclosures on the electricity intensity of their plants. This understates the real weight of electricity in the company’s cost structure, since for example, in the US, they source power wholesale in MISO and pay local utilities (e.g. Kenergy) to deliver it. Conversely, the power prices they highlight in their decks and sensitivity tables are wholesale only.

In the aluminum industry, bauxite is mined and refined into alumina (aluminum oxide), which is smelted to produce aluminum metal. Aluminum metal is cast into basic shapes (“semi-manufactures,” or “semi-finished aluminum”) and/or value-added products which can be sold at a premium to unfinished aluminum.

Unfortunately, Century’s margins are no longer fully comparable to Norsk or Alcoa’s aluminum segments, since the company acquired a 55% interest in the Jamalco bauxite/alumina JV in May 2023. In the most recent quarter, there was about ~$40mn in alumina sales running through Century’s income statement. Dividing total sales by aluminum metal shipments would yield a higher average price per tonne than the company’s average realizations, which are the LME cash aluminum price plus the MWP for its US output, and the LME price plus the European delivery premium for its Iceland plant.

Century’s investor communications anchor on MISO Indiana Hub pricing as a reference point for its US business.