Moving targets

IOC climate goals compared

The integrated oils (IOCs) have been a frequent target for activist shareholders in recent years.1 From 2019-24, shareholders of ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies, and BP voted on a total of 50 resolutions calling for the companies to disclose environmental data and set climate targets. Partly because of their size, and partly because SEC rules make it easy for small shareholders to submit proposals at a US company’s annual meeting, 16 out of the 50 proposals were directed at Chevron, and 23 at ExxonMobil. In aggregate, just 5 won the support of a majority of shareholders, and two of those were not contentious, having been endorsed by management.2

In other words, all of the proposals that won a contentious vote did so in 2021. On average, across all five companies, support for these resolutions increased from 30% in 2019 to 47% in 2021, and fell to just 15% by the 2024 proxy season, earlier this year.

(CAS analysis)

These 50 proposals cover a wide variety of topics that were filed by organizations ranging from state pension funds and European asset managers to unions, campaigning NGOs, and religious orders. What, if anything, can be said about these proposals as a whole? They all invoke the idea that continuing to invest in the oil and gas business — and especially upstream — is risky. On one level this is obviously true in a cyclical and asset-heavy business, and is why IOCs have traditionally talked about allocating capital to upstream projects with a 15-20% or higher hurdle rate. The argument that nearly all of these shareholder proposals have made is that these companies face new and previously underappreciated risks from climate change and the energy transition (i.e. the technological, economic, and political response to climate change).

For example, a 2021 proposal that won 48% support at ExxonMobil’s annual meeting calls for the company to analyze the impact of a specific, accelerated-transition scenario (the original IEA Net Zero by 2050 report) on the company’s financial assumptions:

“As evidence of the severe impacts from climate change mounts, policy makers, companies, and financial bodies are increasingly focused on the economic impacts from driving greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to well-below 2 degrees Celsius below pre-industrial levels (including 1.5C ambitions), as outlined in the Paris Agreement;

This focus has led many ExxonMobil peers (including BP, Eni, Equinor, Repsol, Royal Dutch Shell, and Total) to commit to major GHG reductions, including setting ‘net zero emission’ goals by 2050;

Investors are also calling for high-emitting companies to test their financial assumptions and resiliency against substantial reduced-demand climate scenarios, and to provide investors insights about the potential impact on their financial statements.”

(ExxonMobil Proxy Statement, 2021)

Whether the externalities generated by any business (in this case, oil and gas emissions) will redound to its owners as financial risk (i.e. cash flows that are lower or more variable than expected) is an analytical question about which reasonable minds may differ. In the case of the oil and gas industry, the answer depends on how, where, and when emissions are generated. In much of the world, and certainly in the parts of the world that produce the lion’s share of oil and gas, policymakers are committed to an “all-of-the-above” energy policy that promotes (or at least does not actively disincent) upstream investment in fossil fuels to promote energy security and other goals.3 A barrel produced in the Persian Gulf does not carry the same “climate risk” profile, at least from the lens of the company extracting it, as a barrel produced in the United States, and a barrel produced in Texas does not carry the same climate risk as a barrel produced in California.

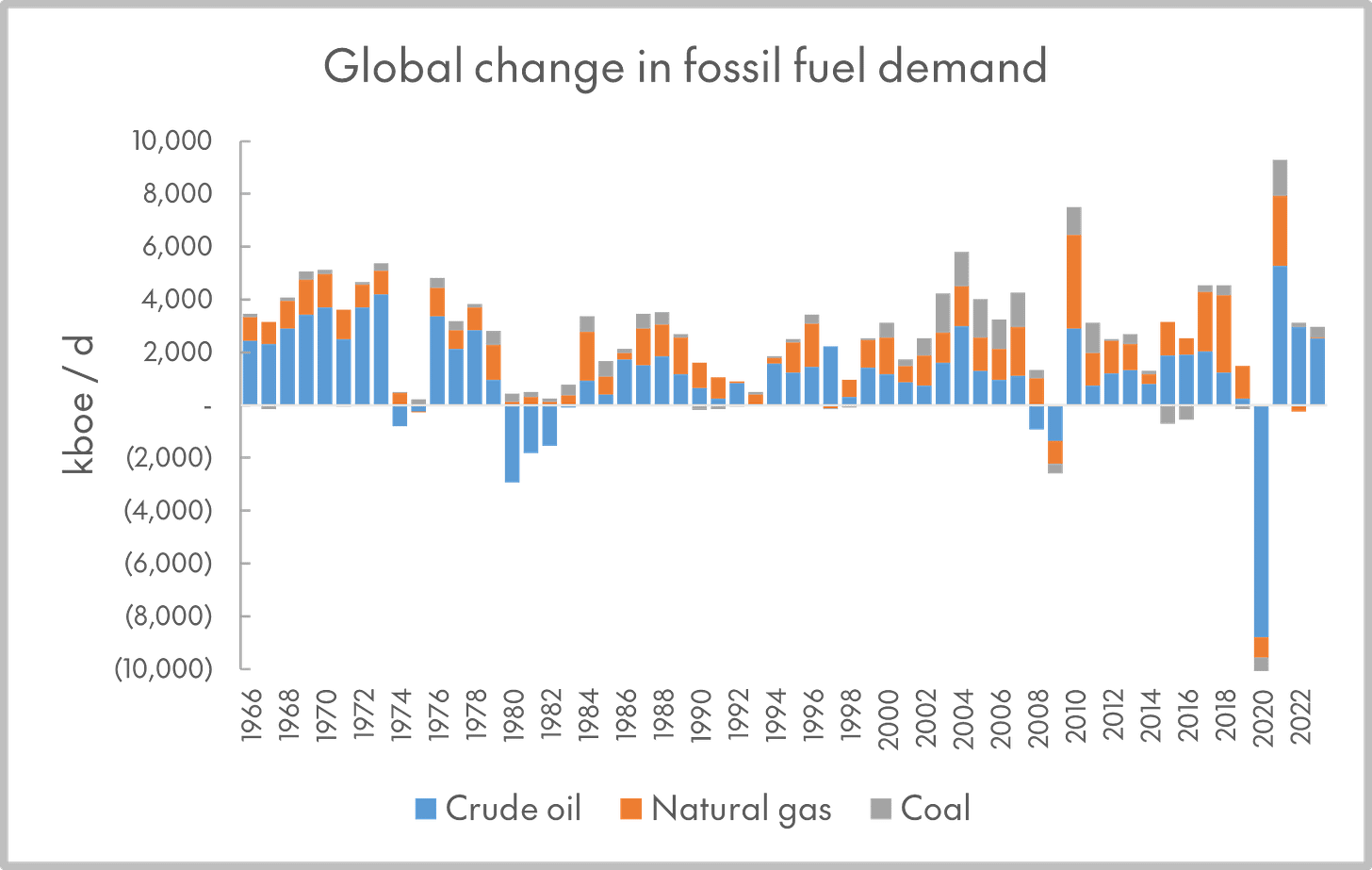

The period from 2016-21 was very unique. The Paris Agreement was drafted in December 2015 and came into effect in 2016. The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures published its recommendations in June 2017. And fossil fuel prices were depressed, averaging < $60 / bbl for Brent (< $70 / bbl inflation-adjusted), compared to > $90 / bbl (> $120 / bbl inflation-adjusted) in the 2010-15 period.4 Capital productivity in traditional energy (measured by returns on capital employed) and unit economics (measured by earnings per oil-equivalent barrel, or BOE) fell to multi-decade lows, even for what had historically been stronger producers (see illustrative data for ExxonMobil below). Finally, COVID itself delivered the coup de grace, with the largest single-year decline in fossil fuel demand in modern history. The conjuncture of all of these factors created an unusual sense of urgency around corporate climate action — and a brief alignment between investors focused on wrangling additional disclosures out of the energy sector to mitigate climate risk to the companies and activists focused on risk to the planet (and a broader constellation of stakeholders).

(SEC filings)

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

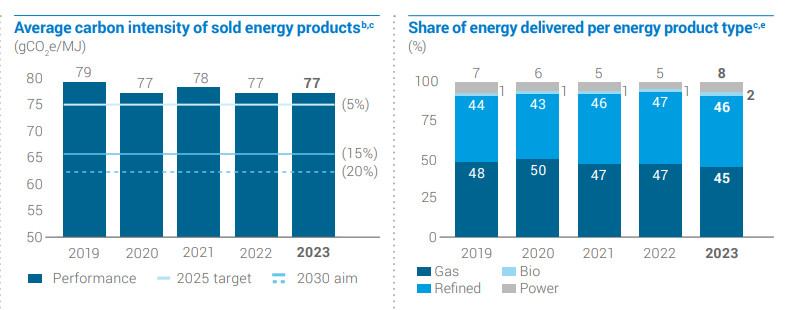

Summarizing the emissions targets these companies have set is daunting given differences in target scope (e.g. operated or equity basis), segmental disclosures, absolute or intensity, base years, and the like. Below, I attempt to do so (see attached .xls file for a more user-friendly version). At a high level, the US majors are focused on reducing the GHG intensity of their upstream assets, with ExxonMobil and Chevron targeting a 40-50% and roughly 40% decline in CO2e emissions per BOE of production, respectively. The European majors (Shell, Total, and BP) all have company-wide absolute emissions targets for Scope 1 (direct) and Scope 2 (purchased energy) emissions, which, in the context of low-single-digit production growth, imply similar intensity reductions. The Europeans also have targets calling for a reduction in the average carbon intensity of energy - 15-20% for Shell and BP, and 25% for Total, including Scope 3 (indirect) emissions.

Each company has a slightly different way of defining this portfolio emissions intensity metric. All of them hope to reach their emissions intensity goal by adding lower-carbon energy sales to both the numerator and denominator, rather than shrinking higher-carbon energy sales. Within the fossil fuel bucket, they expect to see mix shift from liquids to gas, which also reduces emissions intensity.

In general, portfolio carbon intensity metrics tend to aggregate businesses where the majors are directly affecting real-world emissions, like upstream, refining, and renewable power, and businesses like trading and retail marketing where that link is much more attenuated. They also focus solely on “energy sales” emissions, which excludes the very large and emissions intensive chemicals businesses operated by Shell and Total.

Shell:

TotalEnergies:

BP:

The targets that the majors have laid out are obviously not ambitious enough for activists, who continue to use oil and gas AGMs as a forum to highlight a lack of climate action on the part of the industry. However they may be enough to mitigate a great deal of the climate risk facing the companies themselves — which, is their intended purpose. The markets, in turn, may be more focused on disclosures, and on the form of climate reporting than the substance of a particular target or strategy. Making a business case for alternative targets (or more aggressive follow through) requires much more conviction than calling for a company to share certain KPIs, and is less of an obvious fit for the shareholder resolution process; however, it’s absolutely worth debating (and engaging companies on).

In a follow-up post, I’ll dig into how to triangulate emissions targets, long-term corporate guidance for production growth, and carbon cost assumptions, to try and estimate value creation from investing in emissions reduction, as a frame for evaluating the economics of these emissions goals

Appendix

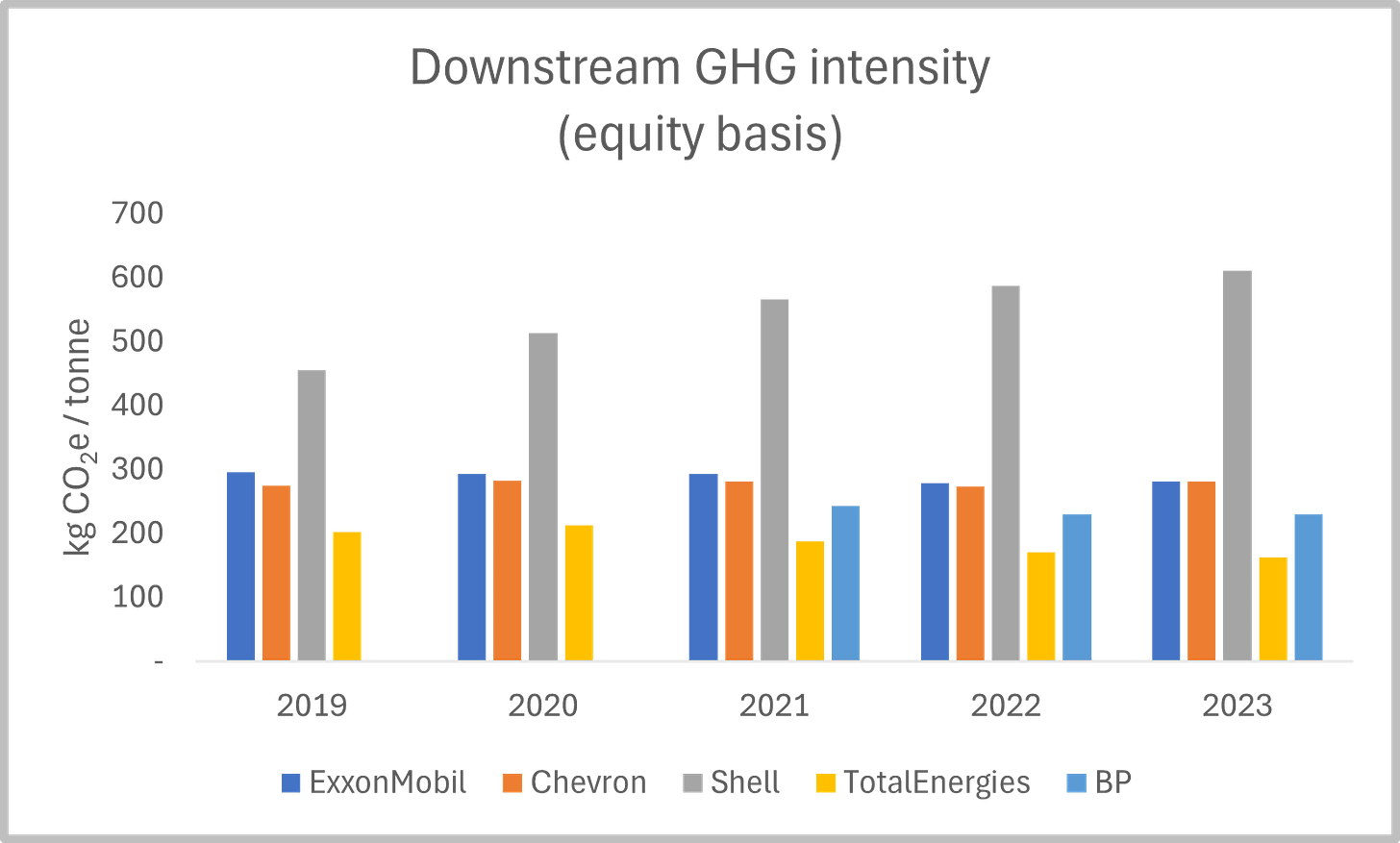

To get a sense of the rough magnitudes, here is a quick look at upstream and downstream emissions intensity across the group, aggregating Scope 1 and Scope 2. Note that “downstream” here aggregates refining and chemicals, and so the numerator is on a per-tonne basis rather than a per-barrel basis (there are a little over 7 barrels in a tonne).

(Company reports)

For the purposes of this piece, I use “supermajor” interchangeably with “integrated oil company,” or “[Western] IOC,” to refer to ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies, and BP.

The BP transition plan resolution in 2019, and the Chevron methane disclosure resolution in 2022.

E.g. affordability, maximizing government revenue, etc.

“Crude oil prices since 1861,” from Statistical Review of World Energy (2024 ed.).