Inputs and outputs

What oil intensity of GDP can and can't tell us

I.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) and OPEC disagree on the medium-term outlook for oil demand. That they should disagree on something is fitting given their histories. OPEC was founded in 1960 amid a wave of decolonization, at a time when non-Western, oil-exporting nations sought greater control over their natural resources, a process that culminated in the creation of many of the national oil companies (NOCs) that exist today. The IEA was created in 1974 as an adjunct of the OECD, the club of high-income, energy-importing nations. OPEC is a cartel of exporters seeking to maximize the long-term oil revenue of its members. The IEA has a more complicated mandate, part of which is to “reduce excessive dependence on oil through energy conservation, development of alternative energy sources and energy research and development.”

Historically, it made sense to talk about the OECD and OPEC as opposite sides of the global oil market - buyers and sellers, respectively. That stylized model has become less accurate thanks to the US shale boom, which has brought the net dependence of the OECD member countries on oil imports to its lowest level in over 50 years.1 However, it is still a decent model to think with. A simple framework for OPEC’s decision making is that it has a certain amount of spare capacity, which members could ramp up to seize market share. The IEA currently estimates spare capacity, including OPEC+ countries, of over 6 million barrels per day (versus global demand of ~103 mbbl/d). OPEC is not incentivized to maximize market share because most of its capacity sits at the bottom of the global cost curve. The Saudi, Kuwaiti and UAE NOCs earn rents from selling their low-cost barrels at oil prices that should, over the long run, reflect the full-cycle costs of the marginal producer, which are much higher. This means that the net impact of increasing OPEC market share can be neutral or even negative, depending on the slope of the global supply curve for oil.

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

OPEC is incentivized to talk up long-term oil demand, because this is the only way for OPEC to collectively grow production volume and revenue per barrel without increasing its share too much, since this can have the destabilizing effect of pricing marginal producers out of the market. On the other hand it is sometimes rational for OPEC to reach for market share in order to discipline higher-cost producers and try to limit supply growth higher up on the cost curve. But the optimal path for oil demand for member states is steady growth that allows the bloc to maintain or grow production without tanking prices.

There are more strategies available to the IEA (as a proxy for the members of the OECD). It is also less obvious how to derive the IEA’s official line from the interests of its member states. While onshore Middle East producers dominate OPEC, the OECD includes both countries like the US, which is the world’s largest oil producer, and, increasingly, a net exporter of oil, and countries like Japan and the member states of the European Union, which are hugely dependent on hydrocarbon imports. But to oversimplify the IEA has two cards to play. It can (1) talk up investment in non-OPEC hydrocarbon supply, or (2) talk down demand. Historically, that meant promoting energy efficiency. Greater energy efficiency means getting more useful work out of the same amount of primary energy and, because of the Jevons paradox, can actually be positive for fossil fuel demand. Increasingly, though, talking down demand means promoting investment in renewables and, technologies like EVs and heat pumps that allow for substitution away from fossil fuels to low-carbon electricity at the point of use. Two potential strategies have become three.

A Financial Times profile of Birol from this August quotes him telling an audience at the energy industry conference CERAWeek back in 2017 that “our message to the oil industry here in Houston is invest, invest, invest.” But in recent years the agency has become more bearish on long-term oil demand and more focused on sketching out the economics of lower-emissions pathways. It makes sense that the IEA is moving in this direction. There are three things it can encourage companies and policy-makers to do: invest more in oil and gas supply; invest in using oil and gas more efficiently; or invest in using alternative sources of energy. The political salience of the last option has gone up and the enabling technologies, especially solar and batteries, have become vastly cheaper. Conversely, promoting non-OPEC oil and gas supply is less urgent because production growth from the shale patch has been so strong anyway. And the relative attractiveness of investing in energy efficiency has not changed much. So in direction, if not necessarily in magnitude, it would be strange if the IEA weren’t promoting renewable investment more heavily than it was 6-7 years ago.

II.

Last month, Fatih Birol penned an op-ed in the Financial Times stumping for the IEA’s prediction that fossil fuel demand will peak before 2030. More precisely, this year’s World Energy Outlook (WEO), the IEA’s flagship long-term forecast, projects a peak in demand “in the next few years” for each of the key fossil fuels.2 Long-term energy forecasts with the imprimatur of a government or inter-governmental agency, like the WEO, is an inherently political project. The goal is to build consensus around a certain level of investment in the energy system.

Birol addressed this directly in the article:

“The peaks in demand we see based on today’s policy settings don’t remove the need for investment in oil and gas supply, as the natural declines from existing fields can be very steep. At the same time, they undercut the calls from some quarters to increase spending and underline the economic and financial risks of major new oil and gas projects — on top of their glaring risks for the climate.”

OPEC responded with a scathing statement criticizing the IEA’s projections. The OPEC response focused on the call to moderate upstream oil and gas investment, given OPEC’s own, far more bullish view of long-term demand.

“It is an extremely risky and impractical narrative to dismiss fossil fuels, or to suggest that they are at the beginning of their end. In past decades, there were often calls of peak supply, and in more recent ones, peak demand, but evidently neither has materialized. The difference today, and what makes such predictions so dangerous, is that they are often accompanied by calls to stop investing in new oil and gas projects.”

What is illuminating about the back-and-forth between the two agencies is that their statements explicitly acknowledge that these forecasts have the power to become self-fulfilling prophecies. Expectations for a certain level of long-run demand feed back into decisions about investing in (1) supply and (2) the equipment that burns fossil fuels for energy (cars, planes, boilers, etcetera).

At the same time, I think it’s important to remember that talking about crude oil demand in the aggregate , whether on an absolute, GDP-intensity, or per-capita basis, can only yield so much insight. This is because of the basic but important fact that, aside from ~1-2 mbbl/d burned each year to generate power in the Middle East, crude oil isn’t used for anything. Oil demand is instead the “derived demand” for the energy services and final goods that oil enables. At the risk of being pedantic I would go one step further and say it is demand for the combination of specific refined products and specialized equipment which can only be used with a particular fuel or feedstock. For oil, this primarily means moving people and goods around in the global economy, and, secondarily, making petrochemicals. In particular, fuels mainly used for transportation - gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and fuel oil - make up the vast majority of oil consumption (at roughly 67%).

The governor of long-term demand for these fuels is the (slow) turnover of the stock of equipment used to transform them into miles of passenger and freight transportation. This process is likely to play out unevenly across different regions of the world and across different end-uses, which is another way of saying, across different refined products.

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

III.

The IEA published its Oil 2024 report in June of this year. The latest OPEC World Oil Outlook came out a few months later in late September. The IEA report calls for 2030E oil demand 7% below the OPEC forecast. In the IEA scenario, oil demand grows by less than ~500 kbbl/d through the end of the decade, while, in the OPEC scenario, it grows by ~1,600 kbbl/d. From a product point-of-view, the biggest variance between the two forecasts is in gasoline and diesel demand, which collectively represents about half of global oil consumption. From a regional point-of-view, the biggest difference is in the OECD Americas (i.e. the US, Canada, Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Chile), followed by the Middle East, and, finally the rest of non-OECD Asia excluding China and India.

Setting aside the political stakes of the broader narrative each agency is promoting, the debate boils down to what happens with road fuels, especially for passenger cars. On a regional basis, it’s about how quickly the US transitions to EVs, and about the fossil fuel intensity of economic growth in the Middle East and in Southeast Asia.

(IEA/OPEC)

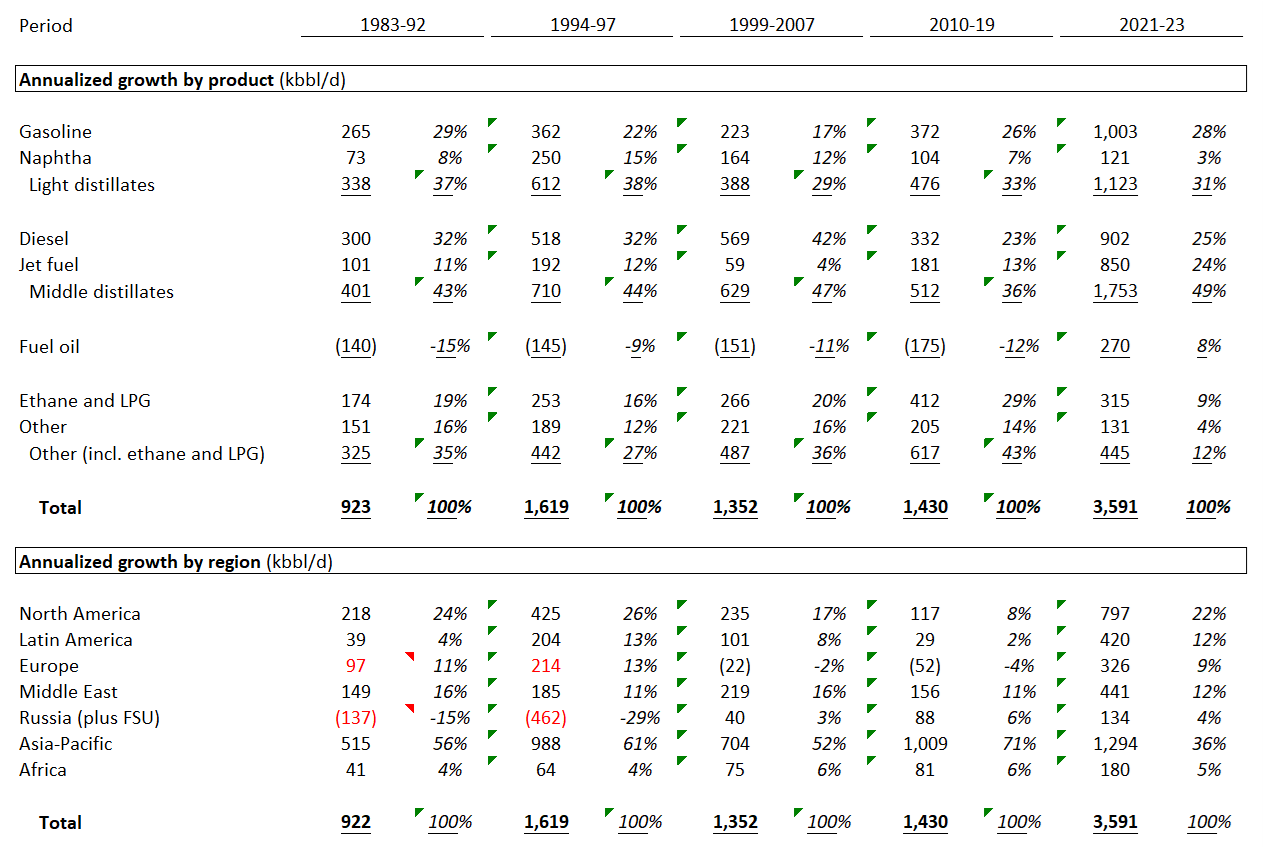

Oil demand has grown very consistently at 1.5-2.0% per year since the early 1980s. On an absolute basis, this translates to ~1,500-2,000 kbbl/d per year from current demand of around ~100 mbbl/d. Interestingly, this pattern of growth has held in across several expansionary periods (1983-92, 1994-97, 1999-2007, 2010-19 and 2021-23) even as the “structure” of growth, i.e. the products and regions driving incremental demand, has varied quite a bit. For example, demand grew by ~1.35 mbbl/d per year from 1999-2007, and ~1.43 mbbl/d per year from 2010-19, a very similar absolute growth rate, while the product breakdown of that incremental demand shifted from 42% diesel to 23% diesel, and Asia’s contribution to demand growth increased from 52% to 71%.3

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

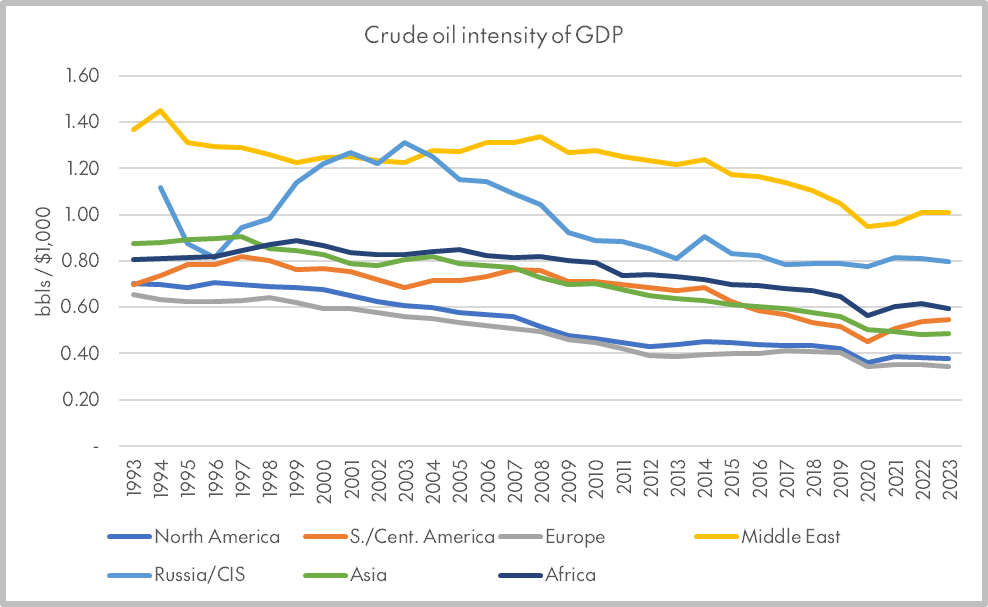

An implication of this math is that over the last ~30 years, the crude oil intensity of GDP, i.e. barrels consumed for each $1,000 in constant-currency output, has steadily declined in every region of the world. It is actually declining faster than the global average in China, India, and other developing countries in Asia (see below chart). However, in general, global per-capita GDP has been growing about as fast as the oil intensity of GDP has been declining. Thus, global oil consumption per capita has been stuck at an incredibly consistent ~4.5 barrels per capita since the early 1980s.

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

The IEA and OPEC scenarios for oil demand through the end of the decade imply a break in this very stable level of per-capita demand — either higher (OPEC) or lower (IEA). The IEA forecast envisions per-capita oil consumption declining by ~0.4% per year from 2023-30, vs. ~0.2% a year for the prior 7-year period. In the OPEC forecast, oil consumption per capita increases by 0.7% per annum. Likewise, the oil intensity of GDP declines by 2.5% a year in the IEA scenario, a slight acceleration from the 2.2% annual decline seen from 2016-23, while in the OPEC model the decline decelerates, to 1.5% a year.4

Past is not necessarily prologue, but I would note that given that demand has not fully reverted back to the pre-COVID trend, with anemic growth over 2019-23 in several regions (Europe, Japan, and North America) and on a product basis, in jet fuel and gasoline. Since the start of the year, OPEC has revised its growth forecast down from +2.2 mbbl/d to +1.9 mbbl/d. Between its Oil 2023 and Oil 2024 reports, the IEA has moved slightly higher, from +0.9 mbbl/d to +1.0 mbbl/d. Anchoring on the latest OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report, demand grew +1.24 mbbl/d in Q1 2024, +1.89 mbbl/d in Q2, and +2.61 mbbl/d in Q3, with +2.33 mbbl/d projected for Q4.

(Statistical Review of World Energy)

But to circle back to an earlier point — the crude oil intensity of global GDP is too overdetermined to serve as a basis for forecasting. It is an output and not an input. Focusing on these aggregates also makes it extremely hard to project the big, non-linear changes coming as batteries continue to make their way down the learning curve and the total cost of ownership for EVs continues to fall. Fighting over 10s of bps of long-term oil intensity CAGR is less productive than, say, rough and ready modeling of regional passenger car fleets based on EV/ICE sales splits and scrappage rates by age.

The point is to refocus the conversation away from a very top-down approach — in which greater per-capita oil consumption appears as the inevitable corollary of economic development — toward a more granular focus on changes in the stock of capital goods and consumer durables that run on oil products. It’s the deployment of technologies that can substitute low-carbon electricity for fossil fuels (EVs, heat pumps, low-carbon pathways in steel and other emissions-intensive industries) that acts as a rate limiter on cutting oil demand. In future posts, I’ll lay out what this analysis looks like for the single largest bucket of oil demand — road fuels.

I am limited here to the period from 1965-2023 covered by the Statistical Review of World Energy.

In the op-ed itself, Birol states that “oil demand is on course to peak before 2030.” The WEO forecast has oil demand growing by ~0.4% per year from 2023 to 2030 in the business-as-usual Stated Policies Scenario (SPS). The agency’s more detailed Oil 2024 report, which is a medium-term forecast, has demand growth slowing from ~1.0 mbbl/d in 2024 to a peak in 2029 and modest (200) kbbl/d decline in 2030.

It is probably worth at least mentioning that it can be very hard to treat supply and demand separately in energy markets. For example, the period from 2010-19 saw much more demand growth in gasoline, ethane, and LPG than in the prior period of growth from 1999-2007, but it is non-obvious how much of this was driven by some kind of inherent increase in demand for passenger car travel and for petrochemicals, versus the increasing availability of lighter products thanks to growth in light tight oil (LTO) supply.

Parenthetically, annual GDP growth is about ~10 bps higher in the OPEC WOO forecast, compared to Oil 2024.