Incentives and outcomes

Revisiting the XOM proxy fight

In March 2021, Engine No. 1, then a small hedge fund1, went activist on ExxonMobil, then, as now, the the largest non-state-owned oil company in the world, producing ~3.8m oil-equivalent barrels a day of hydrocarbons and selling ~4.9m barrels a day of product (gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, etc.) through its refining and marketing operation. Three out of Engine No. 1’s four nominees won board seats at ExxonMobil’s annual meeting that May - Kaisa Hietala, Greg Goff, and Alexander Karsner. Hietala had been EVP of the renewable business at Neste Oyj, a Finnish refiner; Goff was CEO of Andeavor, a US refining and marketing business sold to Marathon Petroleum in 2018; and Karsner was a clean-energy investor and former Assistant Secretary of Energy.

EN1’s successful proxy fight was seen as a victory for “climate activists,” “ESG,” and “impact investing.” A sample New York Times headline: “Exxon’s Board Deafeat Signals the Rise of Social-Good Activists.” This reaction reflected the broader mood of the post-pandemic, pre-energy-price-shock moment in early 2021. As the Times piece points out, earlier that year, Larry Fink’s widely read “Letter to CEOs” declared “there is no company whose business model won’t be profoundly affected by the transition to a net zero economy.”

There are two charts that translate what this looked like in “vibes” terms to financial reality. The first is a comparison of the cumulative, buy-and-hold return of owning ExxonMobil stock (XOM) vs. an S&P 500 index fund (SPY).

And the second is flows into sustainable2 mutual funds and ETFs in the US:

The ExxonMobil proxy fight won EN1 a great deal of notoriety, though financial journalists are still debating what it accomplished. ExxonMobil’s annual meetings have been a major flashpoint for investor activists in recent years, with an increasing number of 14a-8 shareholder proposals making it to a vote — 7 in 2022, 13 in 2023, and 4 in 2024 (two proponent groups withdrew their proposals in 2024 in response to a lawsuit by ExxonMobil). These proposals, which typically take the form of non-binding requests for management to disclose certain ESG-related data (e.g. on climate risks or social impact), or for the board to change the company’s by-laws, have come from both traditional investors (e.g. Legal & General and state pension systems) and mission-driven investors with a more values-based approach. A DealBook column from May 2023 quotes a few investor activists, all of whom criticize Engine No. 1 for a perceived lack of impact on ExxonMobil’s climate strategy:

Whether these assessments are fair depends on your view of what EN1 was trying to achieve in its activist campaign. A year after its nominees won their seats, EN1 itself concluded that the campaign was a success on its own terms. At the most basic level, ExxonMobil stock was up around ~67% between its 2021 and 2022 annual meetings, in line with the energy sector (XLE appreciated ~70%), while large cap US stocks were flat (S&P 500 -1%) and small caps were down (Russell 2000 -17%). So on a one-year look-back, ExxonMobil did very well, if no better than its closest peer, Chevron (up 72%) and in line with the broader sector. The company introduced a range of new climate disclosures and targets. It also created a new, discrete “Low Carbon Solutions” business line, though I would note, as of the company’s most recent 10-K, for financial reporting purposes, “Low Carbon Solutions is included in Corporate and Financing as the business continues to mature through commercialization and deployment of technology.” This suggests that LCS isn’t even losing an impressive amount of money — otherwise ExxonMobil would probably break it out, to encourage investors to look at it separately from core earnings.

(Engine No. 1 - note this piece is from mid-2022)

But all this is somewhat incidental to the case EN1 made in the “Reenergize Exxon” campaign, which, to summarize based on the firm’s May 2021 deck:

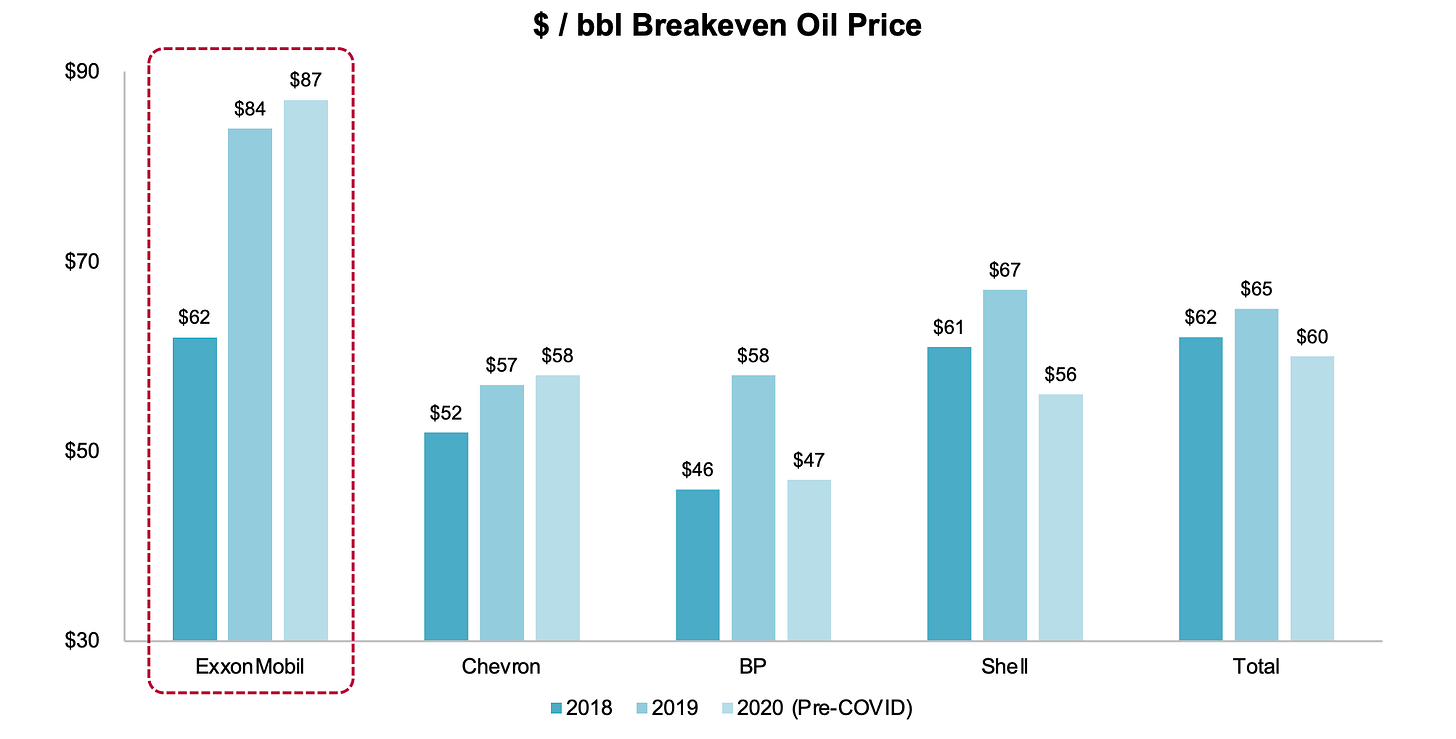

(1) ExxonMobil had underperformed peers and the wider market “over any relevant time period.” This was (the deck argues) because of poor capital allocation, which manifested in many different data points, including the company’s high breakevens - the oil price required to make a profit and fund its generous dividend (nearly $15b a year in 2020, greater than the company’s trough cash flow from operations).

(Engine No. 1 / slidebook.io)

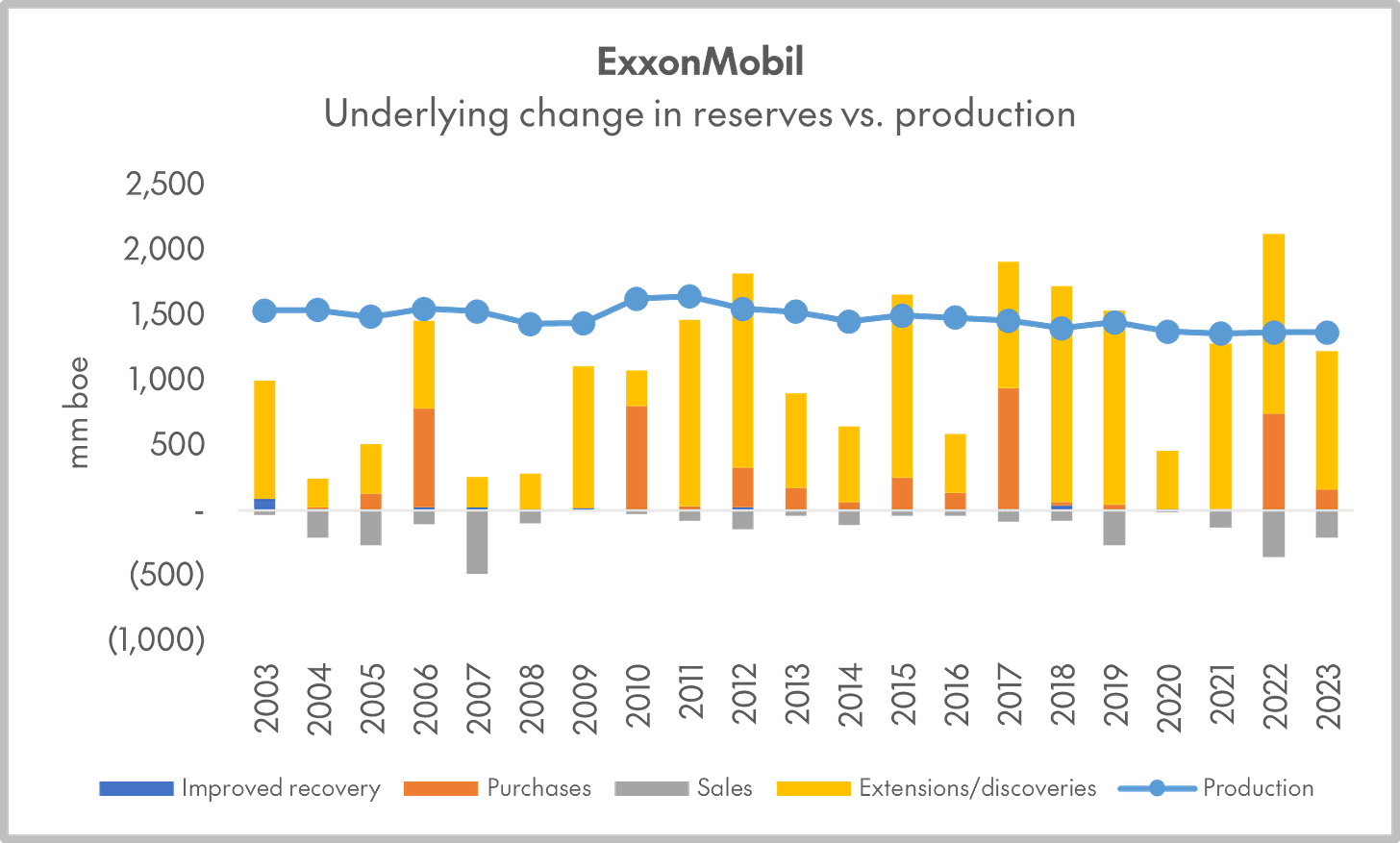

Other metrics featured in the EN1 presentation include oil and gas production per $1,000 of capital employed, which fell from ~39 oil-equivalent barrels in 2001 to ~8 in 2020, and overall return on average capital employed (ROCE) for ExxonMobil’s upstream business, which averaged 39% during the 2000s commodity supercycle (2003-9) and just 5% in the post-shale revolution era (2015-20) despite similar nominal oil prices.

All of these data points are different ways of framing the same economic reality. An upstream oil and gas business invests money in exploring for and developing oil and gas reserves. Most of these costs are capitalized — they first go onto the balance sheet, where they add to the denominator in ROCE, and then are recognized on the income statement over time as expenses when oil and gas is extracted.

(ExxonMobil annual reports; note 2020 includes a large impairment charge within depreciation, depletion and amortization)

The economic cost of producing a barrel of oil, before interest, income tax, or allocating corporate overhead, is (1) the cash cost of extraction, (2) ad valorem taxes, and (3) the current cost of replacing the barrel with additional reserves, i.e. the level of capital expenditure (or M&A spending) required to maintain a constant level of production. Oil and gas prices are hard (arguably impossible) to predict, but through-cycle returns are ultimately dictated by these longer-term trends in per-barrel economics, which is why EN1 highlighted them in its presentation.

(ExxonMobil annual reports)

(2) ExxonMobil lacked a credible climate strategy. One of the more vivid points raised in the “Reenergize Exxon” presentation is that ExxonMobil’s emission reduction targets excluded Scope 3 (use of sold products) emissions, which represent ~90% of the company’s full value chain emissions. But as with the discussion of capital allocation, this was framed in terms of protecting shareholders’ investment in ExxonMobil, not combatting climate change for its own sake. The argument was essentially that management had been poor stewards of value in a world of growing oil and gas demand, demand growth that, per some forecasts, may grind to a halt by the end of the decade (and, to keep global warming below 2C, must tip into long-term decline).

(Engine No. 1)

(3) Fittingly, for a traditional proxy contest, EN1 blamed these issues on a lack of energy sector expertise in the boardroom. Two of their candidates, Goff and Hietala, had been transformative leaders of downstream oil and gas businesses, one, Karsner, was a long-time energy investor and strategist, and the last, Anders Runevad (who did not win a board seat), had been a very successful CEO of an energy-related capital equipment company (the wind turbine manufacturer Vestas).

The final piece of the puzzle — one that gets much less attention in the many retrospectives that have been published on EN1’s campaign — is how EN1 thought its board nominees could help shift both ExxonMobil’s climate strategy and its approach to capital allocation in the right direction. Again, they followed a typical activist playbook, arguing that better designed incentives for ExxonMobil’s senior leadership would drive value creation.

(Engine No. 1)

ExxonMobil’s senior leaders are paid based on long-term stock awards, which vest in two tranches, over 5 and 10 years. This represents ~70% of compensation. Annual cash bonuses, based on a range of metrics, represent ~10-20% of compensation, and salaries the remaining ~10%. The long-term vesting feature of the stock grants is commendable, particularly given the median tenure of an S&P 500 CEO is now under 5 years. The company has long framed this feature of its equity program as a tool to align the time horizon of executives with the average life-cycle of an upstream oil-and-gas project - as illustrated in its most recent proxy statement:

(ExxonMobil proxy statement)

As an aside, an interesting unresolved debate here is on the utility of a more formulaic approach to vesting these long-term equity grants.

Note the first bullet point in the Engine No. 1 slide (emphasis added):

“Consistent metrics with disclosed preset weightings and targets, with more cost management and balance sheet-focused metrics.”

And compare this to the third bullet point in the excerpt from ExxonMobil’s proxy:

“An alternate formula-based program would require a shorter time horizon to set meaningful, credible targets.”

Compare this to Chevron’s long-term incentive plan for executives, which is a mix of “performance shares” (50%), restricted stock units (25%) and stock options (25%). The performance shares are formulaic and based on Chevron’s trailing 3-year total shareholder return (70% weight) and relative improvement in return on capital employed (30%). The RSUs and stock options vest ratably over three years. The major differences with ExxonMobil’s plan is the shorter time horizon, both in terms of the historical look-back and the vesting of stock based compensation, and the inclusion of a specific metric other than total shareholder return.

In sum, what stands out in a review of the original Engine No. 1 presentation is how well the opportunity fit the classic large-cap activist playbook - to paraphrase, (1) management is destroying value via (2) poor capital allocation, and (3) they are doing this because of ineffective board oversight or misaligned incentives. Fix the board oversight and the incentives, and capital allocation will improve, driving higher returns on capital and a re-rating in the stock.

This framework fits very well with the concept of “transition risk.” One component of transition risk is the risk of malinvestment - spending too much to build high-carbon assets that will not earn an adequate rate of return under more aggressive policy scenarios. It can also be thought of as the risk of underinvestment - not spending enough to decarbonize certain activities that could become less competitive under same (e.g. if carbon tax exposure increases). Both issues get right to the heart of long-term value creation — essentially, they amount to applying a climate- and policy-aware lens to capital allocation. And the core problem of ensuring good corporate capital allocation is the agency problem of ensuring management is aligned with long-term shareholders.

Over the next few months, we’ll be spending more time at CAS writing and thinking about how managing transition risk can be better integrated into executive compensation. There are many potential levers here for investors to have a positive impact short of a full-blown proxy campaign, whether through engagement or voting (e.g. on “Say on Pay” and, in extremis, on the re-election of a board’s compensation committee). Attending to compensation and capital allocation as a means of enhancing returns and responsibly managing climate risk is, in some ways, the most logical way to build on the success of Engine No. 1’s campaign — and one that has gotten surprisingly little attention amid the hue and cry of the ESG wars.

As defined by Morningstar.