How much of the US's emissions come from the S&P 500?

A first stab at reconciling EPA data with corporate reporting

More and more publicly traded companies are reporting their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and targeting some level of emissions reduction. 455 out of 500 companies in the S&P 500 index (henceforth, “SPX”) now report their annual emissions, and, per Bloomberg data, 359 of these companies, representing 90% of the index’s reported direct (“Scope 1”) emissions, have some kind of emissions reduction policy in place. Why this is happening is debatable: one could point to the 2015 Paris Agreement, the 2019 Business Roundtable statement on “stakeholder capitalism,” the wave of inflows to sustainable mutual funds and ETFs that peaked in 2021, or, finally, the overwhelming physical reality of climate change.

Whatever role these underlying trends have played, there’s no doubt that pressure from institutional investors has been important. Here’s a representative snippet from BlackRock’s “Global Principles”:

“It is our view that climate change has become a key factor in many companies’ long-term prospects … Specifically, we look for companies to disclose strategies they have in place that mitigate and are resilient to any material risks to their long-term business model associated with a range of climate-related scenarios, including a scenario in which global warming is limited to well below 2°C, considering global ambitions to achieve a limit of 1.5°C” (p. 13).

There are a lot of interesting assumptions here (and in the analogous documents put out by Vanguard, State Street, various pension funds, etc.), and rather than unpacking them at length, I’ll just use this quote to illustrate the influential view that companies can and should meaningfully cut their GHG emissions, and (importantly) that this can be a win-win solution, since over time governments will enact more stringent policies to punish users of fossil fuels and contain global warming to the “well below 2°C” [above preindustrial levels] goal set by the Paris Agreement. Thus, the thinking goes, companies can invest to reduce emissions (via greater energy efficiency, “electrifying everything,” clean power procurement, etc.) now in order to avoid the negative impact of carbon taxes or prices later1.

One problem with corporate emissions reporting, however, is that it’s not very useful for identifying (i) the levers individual companies have for reducing their emissions, let alone (ii) comparing them to the actual building blocks of emissions reduction, i.e. technologies for decarbonizing specific, emissions-intensive value chains, and, where necessary, the policies to help these technologies get to commercial scale (and cost-competitiveness).

What I mean by this is really simple – if you look at something like the EPA’s Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, what you see is a myriad of material flows that, in the aggregate, basically represent the entire US economy, from Zinc production to solid waste disposal and “manure management” (83.4 MT CO2e in 2021). By contrast, if you look at a large, public company’s sustainability report, you see a bunch of cherry-picked KPIs that aren’t readily comparable across companies or industries, and highly aggregated emissions and energy data, e.g. total direct and purchased-electricity (“Scope 2”) emissions, total energy use, etc.

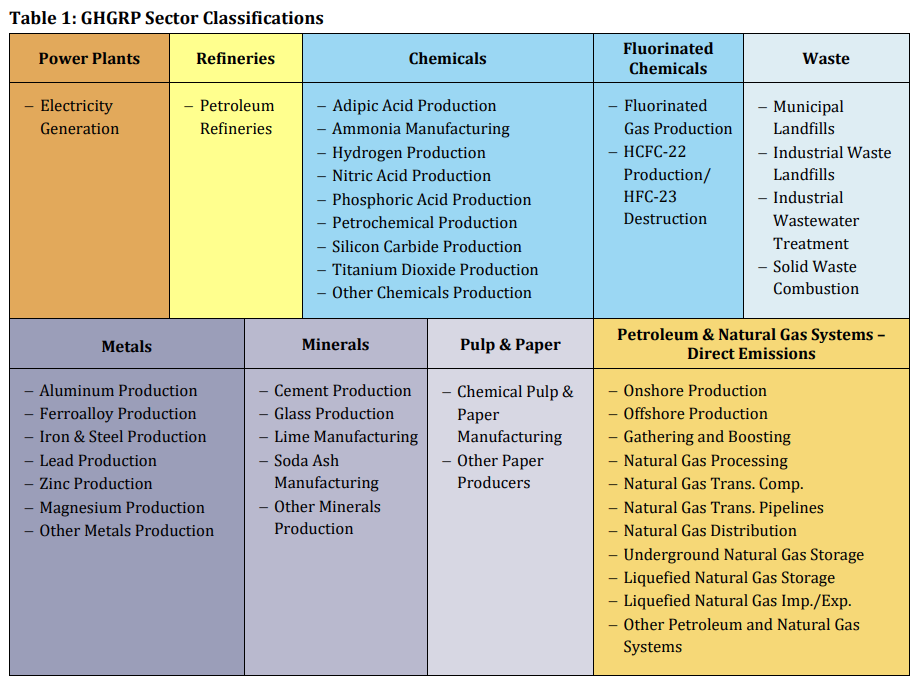

Source: US EPA

To get around this, I built up a simple data set combining site-specific emissions data from the EPA’s GHG Reporting Program (GHGRP) with reported Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions for the S&P 500. The GHGRP covers sites with over 25 kt CO2e in annual emissions, representing about 2.69 Gt CO2e in total emissions for 2022, or approximately 42% of gross US emissions. Using EPA’s parent company data, I found matches in GHGRP data for 69 S&P 500 constituents, representing 82% and 42% of the index’s sustainability report emissions (i.e. global totals) for Scope 1 (1.2 Gt) and Scope 2 (0.1 Gt), respectively.

For the remaining index constituents that were in the top 300 by reported emissions (> 99% of index emissions), I estimated US Scope 1 emissions by the percentage of sales or other relevant metric (e.g. available seat miles, employees, PP&E) located in the United States. For the bottom 200 (< 1%) I applied the average US emissions share (either actual or proxied) of the top 300 emitters (69%). In all cases, I used the same ratio of US-to-global emissions for Scope 2. Finally, I netted Scope 2 emissions from all sectors besides utilities against the utility sector’s Scope 1 emissions, to offset the double-counting of emissions from electric power.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Bloomberg, US EPA

In aggregate, direct S&P 500 emissions – which represent the emissions of the large public companies that are the main focus of conversations on “corporate sustainability,” environmental disclosures, etc. – represent just 17.4% of total US emissions, or 11.5% excluding the electric power sector. A little under half of those emissions come from a few key activities – transportation (98.7 MT), oil and gas production, transportation, and refining (83.0 MT), petrochemicals (42.8 MT), waste (26.5 MT), ammonia (20.6 MT), pulp and paper (19.0 MT) and iron and steel (14.6 MT).2

Note that this presentation of the data shows a lower total because it excludes electric power sector emissions.

Another takeaway is just how top-heavy emissions are. Here’s cumulative emissions as you go down the list – only 142 companies in the S&P 500 produce > 1 MT of emissions each year globally, and just 119 produce that much within the US.

While the utility sector represents the second largest chunk of US emissions (1.6 Gt), S&P 500 utilities only equal 36% of this total, and, in fact, the reported Scope 1 emissions of all publicly traded utility stocks in the US only equal 50% of this total. In other words, municipal, co-operative, and closely-held investor-owned utilities need to play as much of a role in power sector emissions reductions as the publicly traded companies that are more often in the limelight.

Finally, it’s important to touch on supplier and customer emissions (“Scope 3,” though note this category can also include other indirect emissions, e.g. from franchised locations). Individual consumers represent, at a minimum, 748 MT of emissions (passenger vehicles and residential real estate), and the agricultural sector represents another 636 MT.

These sectors are too fragmented to tackle through reporting-and-targeting except indirectly, by selling EVs, retrofitting buildings, etc., and at least from an impact perspective, there’s a case to be made for influencing “consumer” emissions via automakers, building products companies, homebuilders, home improvement retailers, etc., and agriculture emissions via food processors, suppliers of capital equipment to farmers (Deere), packaged food companies and retailers.

But the question should be whether Scope 3 (or derivative metrics e.g. emissions intensity incorporating Scope 3 in the numerator) improves decision-making relative to metrics that are tailored for these industries, particularly given well known quality issues with Scope 3 accounting (e.g. the widespread use of generic emissions factors instead of bottoms-up data collection, companies may choose to disclose non-comparable emissions categories, etc.)

Three implications worth drawing out here – the cost/benefit calculation for a company deciding whether to invest in emissions reduction depends on (i) the timing and uncertainty around future climate policy, (ii) where emissions occur (i.e. policies currently vary, and will continue to vary, across jurisdictions), and (iii) price elasticity of demand (as with any tax).

These estimates are based on my own hand-coding of companies by primary activity – in order to avoid double-counting, I only included pure-play companies that clearly fall into one of these categories. Note that I excluded the vast majority of cruise ship emissions in the absence of detailed breakdowns of sailings by domestic/international, with the exception of Carnival, which breaks out Alaska itineraries (8%).