Clean energy investment, AI power demand, and wet bulb temps

What we're reading about, 6/7/24

Programming Note: Congrats to Anna Hope Emerson, our research fellow emerita, who’s wrapped up her fellowship term with us (and graduated with her MA in economics from the New School for Social Research). She’s now off to work on Mariana Mazzucato’s team at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose - we’re wishing her the best!

(1) The International Energy Agency (IEA) is out with the latest edition of its annual report on investment in the world energy system (World Energy Investment 2024). The biggest takeaway is that clean energy investment is now almost twice the level of investment in fossil fuels, globally. The IEA’s math exaggerates the low-carbon share of energy investment a little, by including spending categories like “grids and storage” and “energy efficiency and end-use,” which are properly fuel-agnostic. But even if you haircut their calculation accordingly, the headline is pretty indisputable - investment in fossil fuel supplies and infrastructure is still well below pre-pandemic levels, while investment in everything else in the energy system is up by about two-thirds.

The other important piece is that the new wave of clean energy investment is playing out in a geographically uneven way. Fossil-related investment is less than a quarter of China’s over $800 billion annual investment in energy-related industries, and an even smaller fraction of Europe’s energy investment. But, in the US, the world’s largest petrostate, it’s still neck and neck with fossil fuel investment.

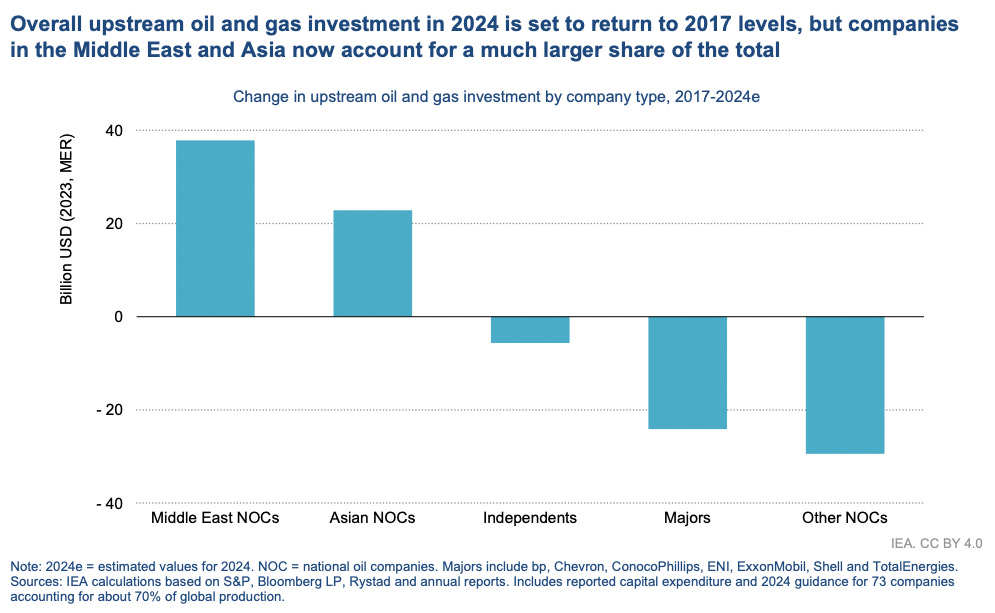

It’s also interesting to map out where “fossil” investment is coming from, and where it’s going, because these patterns have shifted a great deal as well. Western oil and gas companies - especially the “majors,” the vertically integrated giants like ExxonMobil and Chevron - are spending a lot less on upstream projects. Instead, investment is being led by Middle Eastern and Asian national oil companies (NOCs).

One irony that flows out of this - as Arjun Murti is fond of putting it, oil and gas is a topsy-turvy industry where what’s bad is good and what’s good is bad. In other words, clean energy OEMs are capital-intensive businesses operating in hyper-growth industries - industries that, I would add, are either already or soon to be led by Chinese manufacturers. As the chart below shows, renewable OEMs currently aren’t earning their cost of capital, while oil and gas companies, operating in relatively capital-starved “sunset industries,” are earning healthy economic profits.

(2) Goldman Sachs estimates that global data center power demand, led by AI workloads, will grow from ~400 TWh in 2023 to over ~1,000 TWh by 2030. This sounds like a lot, but it’s important to put the finding in context - globally, electric generation was around ~30,000 TWh in 2023 (per the IEA’s Electricity 2024 report).

In the post-pandemic recovery, global electricity supply has been growing roughly ~2.0-2.5 percent per year (so ~500-700 TWh), and the IEA forecasts that from 2023 to 2026, growth will accelerate to a little over 3 percent per year (~1,000 TWh). IEA’s bridge from 2023 to 2026E supply assumes big increases in renewable generation (+3,200 TWh), more modest increases in nuclear (+218 TWh) and gas (+146 TWh), with declining coal and “other non-renewable” generation (-600 TWh).

The problem for AI energy demand maximalists is that this growth trajectory is already embedded in the IEA’s numbers, which actually envision faster growth than the Goldman analysis highlighted above (IEA’s base case looks to be pulled forward by about ~2 years).

Nevertheless, the prospect of rapid growth in energy demand from data centers is getting some analysts bullish on natural gas. The thinking is that hyperscalers will want 24/7, “dispatchable” power, and more gas capacity is the only way to get it at a reasonably low cost and short lead time. In his essay “Situational Awareness,” the AI influencer Leopold Aschenbrenner rolls out this table with back-of-the-envelope calculations on future AI power demand. Note that in Aschenbrenner’s parlance, an “OOM” is an order of magnitude (a 10x increase in intelligence).

Note the assumption - that power demand scales linearly with “OOMs” (which I assume are supposed to scale linearly with compute). Has this been the case historically? Absolutely not, as a somewhat dated but still very interesting Berkeley national lab report highlights. Energy efficiency gains fully offset increased demand for computing power throughout the 2010s.

Per the Goldman report cited above, actual US data center power demand in 2020 was ~86 TWh. The national lab report’s estimate was 73 TWh - which, while a little bit of an underestimate, was a lot more accurate than extrapolating linear power demand growth into the future.

(Lawrence Berkeley National Lab)

There’s a lot more to be said on these topics, and a lot of technical material I have yet to master, so stay tuned for a future deep dive. But as a parting note, I would just highlight this slide from Jensen Huang’s Computex 2024 keynote last Sunday:

(NVIDIA via YouTube)

Further Reading:

Temperatures in Delhi and Rajasthan reached 122F this March, part of a heat wave that experts say is responsible for hundreds of deaths (Reuters).

AMLO protégée Claudia Sheinbaum - trained as a climate scientist - cruises to victory in the Mexican presidential race (Bloomberg).

Andrew Elrod interviews Eurasia Group’s Gregory Brew on the Red Sea as a chokepoint in world oil markets (Phenomenal World).

Is the unchecked spread of rooftop solar panels a sneaky form of regressive taxation? (Heatmap)

In a typically bizarre and inexplicable about-face, New York governor Kathy Hochul backs out of a plan for congestion pricing at the last second (New York Times).